I have always been interested in family histories: my

family, other people’s family, it doesn’t really matter. What matters to me are

the stories of the people that came before us; that’s probably why I became a

historian. So, imagine my delight when, just a few weeks into my position at the

Geary County Historical Society last year,

I came across an entire family history collection that had been donated

to the museum and was waiting to be added to the system! Everything from baby

clothes to original German immigration documents greeted me when I opened the

box—and so began my love affair with the Oesterhaus family.

The story of the Geary County Oesterhaus family starts

with Dietrich “Hermann” Oesterhaus. Hermann was born on June 2, 1821 in

Heerseheide, Germany. As a young man, he married Philopena Caroline Justine

Blanke before they immigrated to the United States in 1852 and settled in

Evansville Indiana. While starting their new life in America, Hermann and

Philopena had five children: Lena, Matilda, Lewis and twins Fred and August.

They stayed a few years in Indiana before they moved their young family to

Kansas.

|

| Lewis Oesterhaus, age 12, Circa 1868 |

In 1867, Hermann and Philopena bought land from Henry and

Hannah Mihleman outside of Junction City. This purchase was just the beginning

of the large land purchases the Oesterhauses would make in years to come.

Now, the Oesterhauses were a large family, so the story

could branch into several different directions, but the story that the museum’s

objects tell is the story of son Lewis Oesterhaus and his family. Lewis met his

wife Mary Klusmire when their families traveled together through Kansas, though

the families did not settle near to one another—the Oesterhauses in Geary

County and the Klusmires in Holton, KS.

Lewis and Mary were married on June 3, 1878 and settled

on Oesterhaus land outside of Junction City. When they celebrated their

anniversary 52 years later, Lewis recalled “the trip [to take Mary from Holton

to Junction City] of one hundred miles meant slow travel with a team and wagon

over narrow, rough roads and fording streams because of few bridges over

them…requiring almost a week to go and return again.” Once they reached Geary

County, Lewis built a stone cottage of three small rooms that they lived in for

seventeen years. Their first child, Anna

Matilda, was born in that stone cottage on March 3, 1880. It was during a

spring blizzard and Lewis was gone, no one was able to come. So, Mary gave

birth alone.

|

| The Oesterhaus children: John, Mabel and Anna circa 1890 |

They eventually had two more children, John and Mabel.

The photographs of the children donated to the museum indicate that Lewis and

Mary Oesterhaus were prosperous. The children were always well dressed and there

are multiple portraits of them throughout their childhood—a sign of wealth in

an age when photography was a luxury.

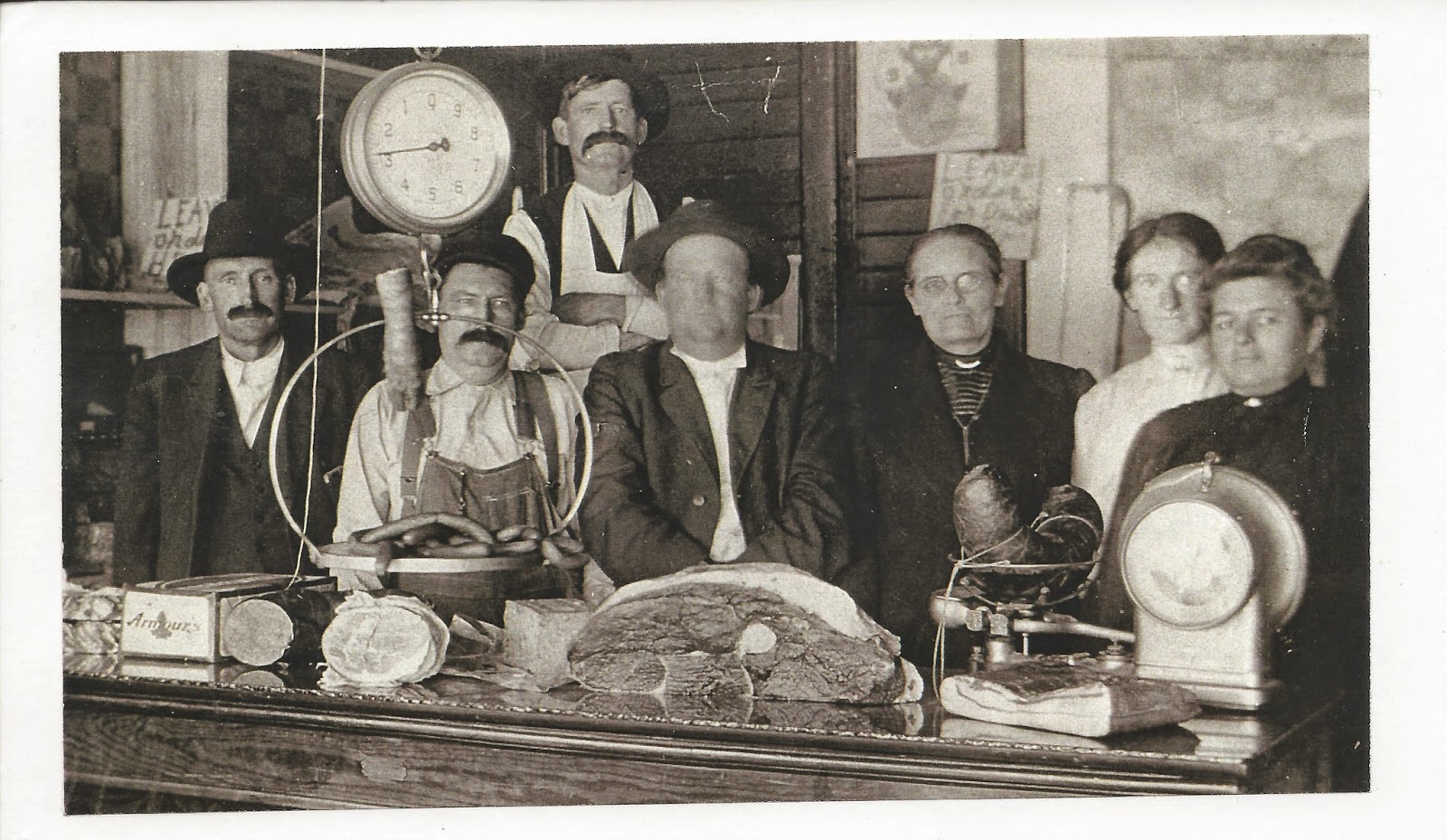

And the Lewis Oesterhauses had a good reason for their

prosperity. At the turn of the 20th century, Lewis Oesterhaus and

his partner, Jacob Winner—a local butcher— had a contract with Fort Riley to

supply the military base with their beef. It is likely that through this

business, Lewis’s daughter, Anna Matilda Oesterhaus, met her husband, Fort

Riley’s beef inspector and cavalry veterinarian, Charles Jewell.

|

| Anna and Charles Jewell on their wedding day December 22, 1906 |

When Anna and Charles were married, Anna wore a dress

made out of Piña—a fabric made out of

pineapple fibers—that Charles brought home for her after he was stationed in

the Philippines. They had one daughter, Mary Jewell. It is Mary Jewell’s

descendants who generously donated so many of the Oesterhaus heirlooms to the

museum.

Lewis and Mary

Oesterhaus’ son, John, attended Kansas State University and became a

veterinarian, later founding the Kansas City Vaccine Company. Youngest

daughter, Mabel, stayed in Junction City. She also attended Kansas State

University before becoming a teacher at several rural schools near Junction

City.

Many of the Oesterhaus

heirlooms are now on display at the Geary County Historical Society in our

local genealogy case, including: German immigration papers from 1850, a large

family photograph of the original Oesterhaus family, a tintype photograph of

Lewis Oesterhaus and the Piña fabric that was used to make Anna Jewell’s

wedding dress. If you have local family history objects or stories, we would

love to talk to you! Open Tuesday-Sunday, 1pm-4pm.